The Clergy of the Church of England Database (CCEd) is a relational database (a database which stores information in multiple tables) which links primary sources relating to the clerical careers of the Church of England between 1540 and 1835. The creators of the database feel its contents are of use to the general public and genealogists but it will be best utilised by political and social historians, wanting to trace individual career paths, understand the structure of the Church of England or determine patterns in clerical migration.

The presentation of the database is simple and clear. The layout is minimal and does not distract the user with garish or numerous images.

One of its best features is the how to use the database section. However, the navigation is a bit cumbersome and it often suggests using another section but does not link to it.

For the CCEd a web database is the most appropriate tool, permitting quick and complicated queries to be carried out from the web page. The ease of updating from any computer and the ability to link records, allow the project to create career narratives for an in-depth analysis of the sources. These narratives save historians the time and hassle in trying to plot the career of clergymen themselves and can quickly show them the major events taking place in clerical careers.

This simple database with limited visualisations would be relatively cheap to create and maintain compared to high-end technical supported databases. But is complex enough to hold a large amount of data (the CCEd contains 1,250,000 individual records).

A big data project (like CCEd) allows for both close reading and distant reading. Patterns and trends in the structure of the church and clerical migration can be ascertained through distant reading. However, we can lose the human element by looking at big patterns; the individual experience can challenge the overall arching trends. Engagement and imagination is an essential part of a historian’s interaction with primary sources and close reading can provide such interaction. However, direct engagement with the primary sources is not facilitated by the database.

Digitisation Methodologies

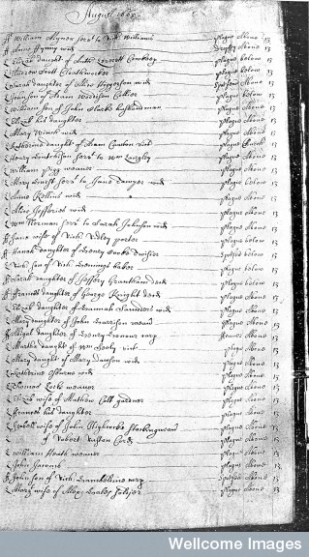

The data capture method of textual input, although time consuming, increases the accuracy of the information captured. Especially when compared to other methods, such as Optical Character Recognition, which struggles with early manuscripts and handwriting (it so renowned for its mistakes there is even a Twitter account satirising it!). However, the selection of only very specific information contained in the primary sources calls into question whether other valuable information has been missed?

Example of OCR Going Wrong. Image from A Report and Review of the Scanning Claim by the Editor at janelead.org (Link via Image)

It is understandable for a project of this magnitude to want to contain only the most essential information but a low resolution page image of the primary source would help the historian feel connected to the primary source without taking up too much storage space.

Although, a page image cannot be searched or manipulated, for the purpose of the database it would not have to be. It could simply function as a standalone feature, adding another layer of understanding to the interpretation of the sources. The image quality would not have to be high either, as long as the source retained its readability when zoomed in.

Instead the user is presented with a ‘screen format’ of the records used, giving the user no feel for the primary source and certainly no engagement with it.

To facilitate the dissemination of work interpreting the records in the database, the website has its own online journal. This is where the website uses XML to facilitate the searching of articles, although it does not provide any transparency in the use of this tool. The limited use of XML is due to the search engine within the database itself which does not have the time consuming disadvantage of having to create building blocks as XML does.

Overall, the database renders the primary sources redundant. The pre-selection of sources and of the information required from them, the presentation of their data in field format, the lack of images of the primary sources and the methods of analysis (record linkage and career narratives) seem to place an emphasis on the database as a source of historical information rather than on the primary sources.

For historians, who like to read the primary sources, the extraction of information must rub against the bone. Could there have been other contextual information that might have been contained within the primary source?

Bibliography of Links

‘Advanced’, Clergy of the Church of England Database, http://theclergydatabase.org.uk/how-to-use-the-database/advanced/; consulted 1st March 2014

‘Big Data for Dead People: Digital Readings and the Conundrums of Positivism’, Historyonics – Tim Hitchcock’s Blog, http://historyonics.blogspot.co.uk/2013/12/big-data-for-dead-people-digital.html; consulted 1st March 2014

‘Bibliography of sources used in the Database’, Clergy of the Church of England Database, http://theclergydatabase.org.uk/reference/bibliography-of-sources-used-in-the-database/; consulted 28th February 2014

‘Close Reading’, University of Warwick, http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/fulllist/second/en227/closereading/; consulted 1st March 2014

Cohen, Daniel J and Rosenzweig, Roy, ‘Appendix – Database’, Digital History, http://chnm.gmu.edu/digitalhistory/appendix/1.php; consulted 28th February 2014

Cohen, Daniel J and Rosenzweig, Roy, ‘Becoming Digital – Digitizing Text: What Do You Want to Provide?’, Digital History, http://chnm.gmu.edu/digitalhistory/digitizing/2.php; consulted 1st March 2014

‘Contents of Database’, Clergy of the Church of England Database, http://theclergydatabase.org.uk/about/about-the-database/content-of-database/; consulted 1st March 2014

‘Data Capture’, University of Oxford, http://digital.humanities.ox.ac.uk/methods/datacapture.aspx; consulted 1st March 2014

‘How to Use the Database’, Clergy of the Church of England Database, http://theclergydatabase.org.uk/how-to-use-the-database/; consulted 28th February 2014

‘Information for Genealogists’, Clergy of the Church of England Database, http://theclergydatabase.org.uk/information-for-genealogists/; consulted 28th February 2014

‘Information for General Public’, Clergy of the Church of England Database, http://theclergydatabase.org.uk/information-for-general-pubilc/; consulted 28th February 2014

‘Interpreting Career Narratives’, Clergy of the Church of England Database, http://theclergydatabase.org.uk/how-to-use-the-database/interpreting-career-narratives/; consulted 1st March 2014

‘Introduction to XML’, W3Schools, http://www.w3schools.com/xml/xml_whatis.asp; consulted 1st March 2014

‘Journal’, Clergy of the Church of England Database, http://theclergydatabase.org.uk/journal/; consulted 1st March 2014

‘OCR (Optical Character Recognition)’. TechTarget, http://searchcontentmanagement.techtarget.com/definition/OCR-optical-character-recognition; consulted 1st March 2014

‘OCR Fail’, Twitter, https://twitter.com/OCRfail; consulted 1st March 2014

Schulz, Kathryn, ‘What is Distant Reading?’, The New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/26/books/review/the-mechanic-muse-what-is-distant-reading.html?pagewanted=all&_r=2&; consulted 1st March 2014

‘Welcome to the CCEd’, Clergy of the Church of England Database, http://theclergydatabase.org.uk/; consulted 28th February 2014

‘What are Relational Databases?’, How Stuff Works, http://computer.howstuffworks.com/question599.html; consulted 28th February 2014

‘When OCR Goes Bad: Google’s Ngram Viewer & The F-Word’, Search Engine Land, http://searchengineland.com/when-ocr-goes-bad-googles-ngram-viewer-the-f-word-59181; consulted 1st March 2014

The CCEd project would like to thank Sinead Finn for this thoughtful appraisal of its site. We’ve noted your comment on the need for more links in the advice on how to use the database, and will seek to address this in the near(ish!) future.

Perhaps we could just comment on your observations on the lack of digital images of the sources? This issue has been one we have long debated with others in the digital humanities community, not least with Tim Hitchcock, until recently himself at the University of Hertfordshire.

All three project directors are dedicated archival historians, and we completely agree with you about the importance of the ‘feel’ of documentation to the historical imagination. Nevertheless, we still stand by our decision many years ago to not include comprehensive images of our sources, even though it was taken at a time when such a decision was much less unusual than it now would be (when we won the grant to construct the database, we envisaged it appearing on CDs, although by the time we started work, the web was obviously a more desirable solution). At the time the costs involved would have been prohibitive: and indeed had we then realised just how many sources we would actually end up entering, it would not have appeared possible to fund the project as it currently stands, for the process of identifying sources that occupied the first eighteen months of the project revealed many issues that we had not anticipated which required new archival strategies to address. While in some ways even then we regretted the consequent emphasis on extracting for databasing, we were conscious that our records were not only formulaic and laconic, but consistently so over the three centuries we cover: thus for most of our records, the ‘missing’ content of the records would be a version of one of perhaps three or four basic formulations which could in a sense be reconstructed around the material extracted. We have always intended to post examples of these source models both in transcription and reproduction, but have for the moment concentrated on making as much of our material as possible available as quickly as possible. In fact, our researches subsequently revealed hitherto unknown degrees of variation in the formulations, so that this task is also a more complicated one than we anticipated, and will require significant care and work, another source of delay. The decision also underlines the fact that we are not seeking to replace the physical archive so much as open it up: there are many document series, for example, which interact with those we have recovered which we were not able to include, and so for questions other than those of central interest to the database makers, it will always be necessary to return to the archives themselves, although CCEd will give its users a much better idea of where to start looking than would have been possible otherwise.

Thank you again for your interesting post, and for taking an interest in our site.

Arthur Burns for the CCEd team